Published in ARTUNER, 11 November 2013

Over the past decade, the art market has undeniably evolved. Remarkably resilient in the wake of the financial crisis, artworks have become tangible assets for international investors. Riding the tide of globalization, a new influx of collectors has emerged within South America, Asia and the Middle East, while the acquisition of art online has provided buyers with an unparalleled level of access to masterpieces worldwide. Needless to say, there is a stark contrast between collecting in the Digital Age and the sixteenth-century practice from which it stems. Yet, investigating the historical genesis of this pastime highlights the emotional, aesthetic and intellectual qualities that continue to inspire collectors today.

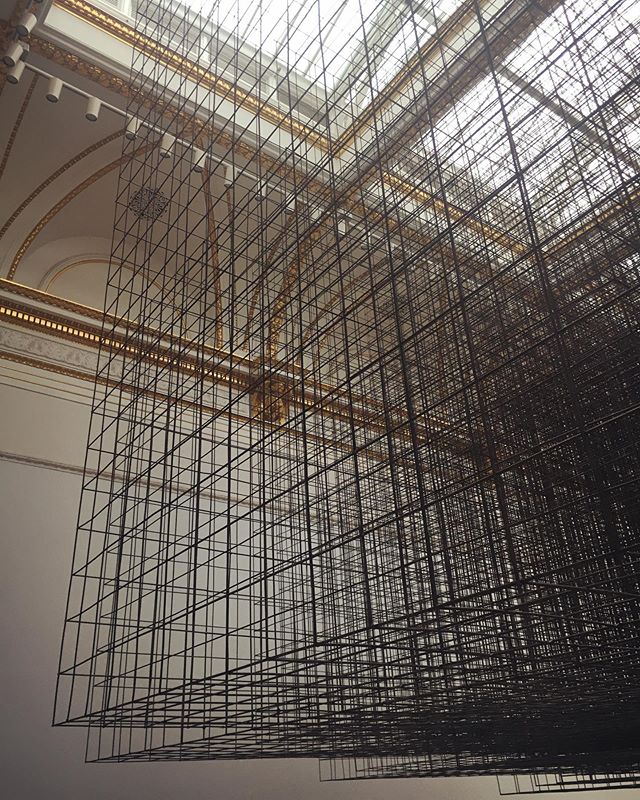

Epitomizing the magnitude and diversity of a sixteenth-century cabinet of curiosities, Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor’s (1552-1612) kunstkammer (or art-room) held 470 paintings, 69 bronze figures, 179 ivory objects, several thousand medals and coins, 403 Indian curiosa, 600 vessels of agate and crystal, 50 amber and coral pieces, 185 uncut diamonds and precious stones, 174 works of faience, 300 mathematical instruments, numerous taxidermies, and countless other items. Arguably the most important collector of his time, the Emperor’s kunstkammer speaks of the breath and depth of collecting during the Renaissance period. While categorical boundaries were yet to be defined, these cabinets of curiosities acted as a precursor to the art of museology and collecting.

A characteristic product of its age, Rudolf II’s encyclopedic collection sought to paint an image of the universe, as it reflected the connoisseur’s pansophical view of the world. Exhibiting works of art and antiquities, as well as the physical world of phenomena, the intent was to amass objects that formed an intrinsic part of the universal system. Thus, elements of natural history, geology, ethnography and archaeology rubbed shoulders with religious relics, paintings and sculptures. These cabinets of wonder morphed into a microcosmic theatre of our macrocosm where collective memory and one’s own personal history were displayed.

Privileging empirical knowledge, a well-rounded experience of the objects through an active involvement of all five senses was fundamental. Olfaction in particular was valued (herbariums, for example, oozed exotic aromas). The devaluation of smell in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries inscribed an important break in the history of collecting, as a palpable shift from the ephemeral to the aesthetic occurred. Philosophers and scientists of that era eulogized sight as the ‘pre-eminent sense of reason and civilization, [while] smell was the sense of madness and savagery.’ [1] A ‘coarse sense’ according to Immanuel Kant, smell saw its demise and visual culture quickly flourished.

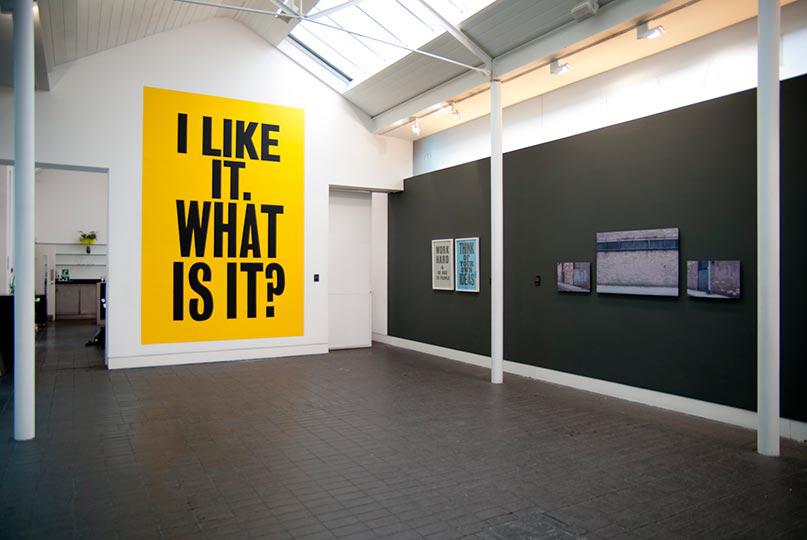

Flowing from this fundamental insight, the attractive presentation of these opthalmoceptive pieces, as opposed to their secretive storage, became integral to the art of collecting. This novel form of exhibitionism expressed collectors’ conviction that displaying their artistic treasures in such a manner was sure to enhance their beauty by the astute juxtaposition of the objects with their setting. The Wallace Collection in London and the Frick Collection in New York, both still on view today in their original dwellings, illustrate this ruptured continuity with their sixteenth-century antecedents.

While similarities between the Age of Discovery’s haphazard kunstkammers and the Romantic era’s lavish displays of art may be few and far between, one in particular can be observed. Cabinets of curiosities frequently featured items amassed from the connoisseur’s travels. Morphing into relics of his life journey, they also bore their own past. Likewise, eighteenth and nineteenth-century collections were inevitably punctured with one’s own story, whilst also communicating each artwork’s provenance, literature and exhibition history. Further illustrating this point is the bequeathment ritual that is common to most, if not all, historical collections, be it of rarities or of art. This simple act of handing down to future generations spoke of the value placed on both the past and the future.

Today we live in an era characterized by technological abstraction. Yet our culture’s priorities, its notion of value, are still intrinsically linked to our relationship with the physical object, the artwork. Collecting has undeniably blossomed since the Renaissance period. With the advent of the Internet, the mediums through which we acquire art have moved into the virtual sphere. However, the factors that determine the collectibility of an artwork have remained unchanged. To quote Iwona Blazwick in last week’s Insight: “Above all you have to be moved by it, be curious about, love, admire, even be confused by the work of art.” Acquiring art grounds us to something tangible; and in this sense, the practice has endured as a physical exploration of both our collective and personal histories.

[1] Classen, Constance, David Howes, and Anthony Synnott. Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell. London: Routledge, 1994, p. 4

Recommended reading

Altshuler, Bruce, ed., Collecting the New, 2006

Arnold, Ken, Cabinets of the Curious: Looking Back at Early English Museums, 2006

Cummings, Neil, and Lewandowska, Marysia, The Value of Things, 2000

Elsner, John, and Cardinal, Roger, ed., The Cultures of Collecting, 1994

Haskell, Francis, Rediscoveries in Art: Some Aspects of Taste, Fashion and Collection in England and France, 1976

Hermann, Frank, ed., The English as Collectors: A Documentary Chrestomathy, 1972

Hook, Philip, The Ultimate Trophy: How the Impressionist Painting Conquered the World, 2009

Impey, Oliver, and MacGregor, Arthur, The Origin of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth and Seventeenth Century Europe, 1985

MacGregor, Arthur, ‘Collectors and Collections of Rarities in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries’, in Tradescant’s Rarities: Essays on the Foundation of the Ashmolean Museum, 1983

Pearce, Susan, On Collecting: An Investigation into Collecting in the European Tradition, 1999

Taylor, Francis Henry, The Taste of Angels: A History of Art Collecting from Rameses to Napoleon, 1948