Published by The Courtauld Gallery, 17 June 2010

The Courtauld Gallery, London

17 June - 18 July 2010

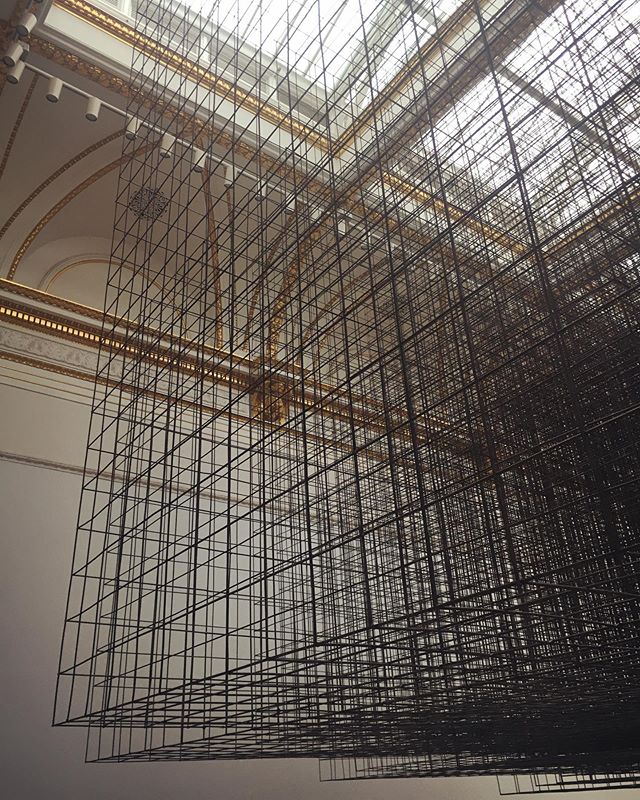

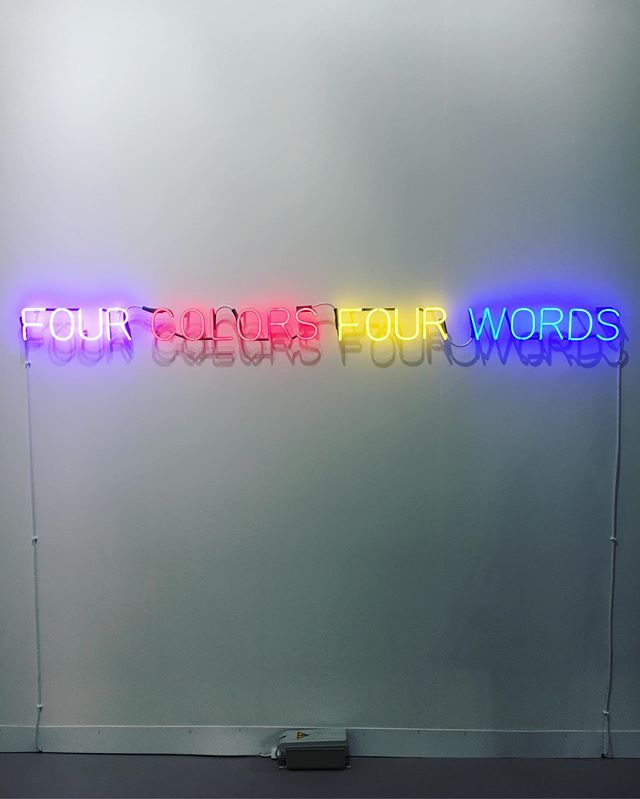

BLOOD TEARS FAITH DOUBT, Historical and Contemporary Encounters draws parallels between works of art from the 15th century to the present day to address themes of suffering, compassion, devotion and belief. It juxtaposes works to provoke an emotive response and to emphasise the continuing power of religious imagery, even in the secular context of the art gallery. This thought- provoking exhibition brings together painting, sculpture, works on paper, photography and decorative arts, and has been curated by students on The Courtauld Institute of Art’s MA programme Curating the Art Museum. Drawn from The Courtauld Gallery and the Arts Council Collection, it includes, among others, Old Masters Polidoro da Caravaggio and Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, and contemporary artists Adam Chodzko, Siobhán Hapaska, and Grayson Perry.

BLOOD TEARS FAITH DOUBT stages two encounters: between the works themselves, sparking dialogue between images of striking or surprising similarity; and between the works and the beholder, whose engagement and empathy with the subject and its portrayal remains central to the enduring power of religious art. The exhibition unites works from the Western tradition of Christian art and contemporary works that resonate with that tradition. It explores how these images were used and viewed historically, and considers whether their appropriation in contemporary art can evoke the same intensity of emotion as they did in the past.

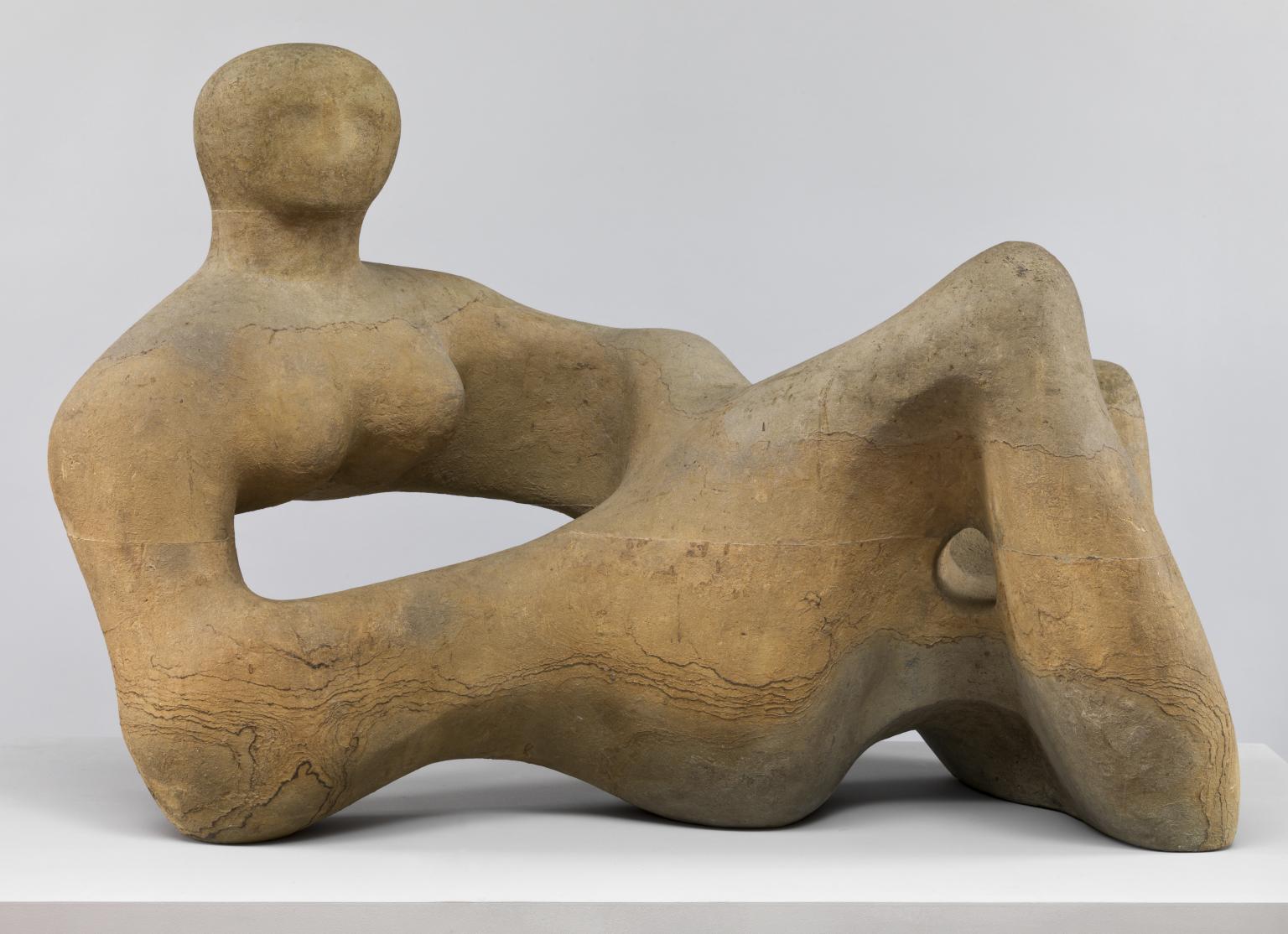

The central themes of BLOOD TEARS FAITH DOUBT are explored in the exhibition in rooms 11 and 12 of The Courtauld Gallery in three sections: mother and child; devotion; faith and incredulity. The first section presents images of the Madonna in various attitudes. She is seen as nurturing mother in Virgin and Child with Saint Jerome (1510-30) by Giampietrino, in Mark Fairnington’s The Greek Madonna (1993), and in the disturbing imagery of Grayson Perry’s Spirit Jar (1994). In Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ (18th century), she is presented as a bereft and grieving figure. The Pietà is further recalled in the sculpted hand holding wilted flowers of Phil Brown’s Untitled (Hand) (1994).

In the pivotal space of the darkened central room, two intimate, small-scale devotional works – Christ Crowned with Thorns by a follower of Dieric Bouts (c.1475) and an ivory diptych (14th century) featuring the Madonna and Child and a Lamentation scene – are presented in a setting which recalls their original function and power.

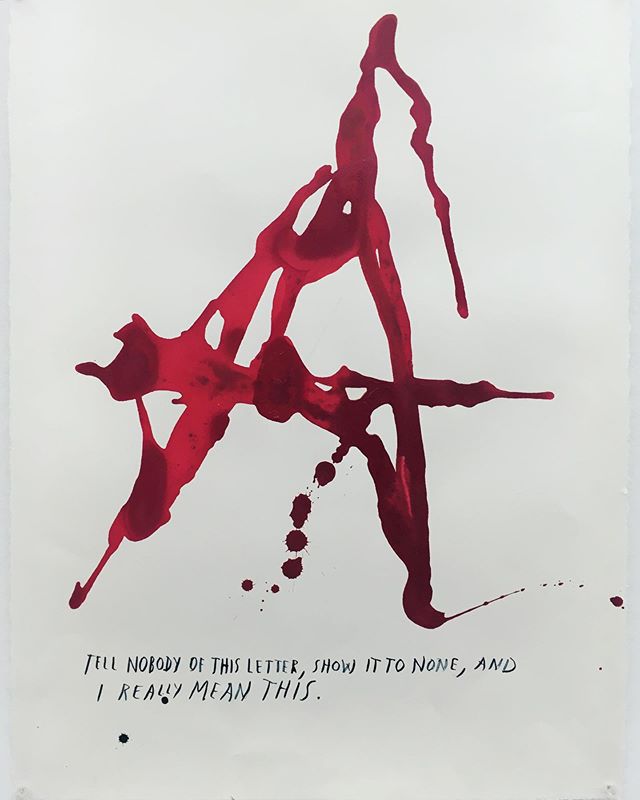

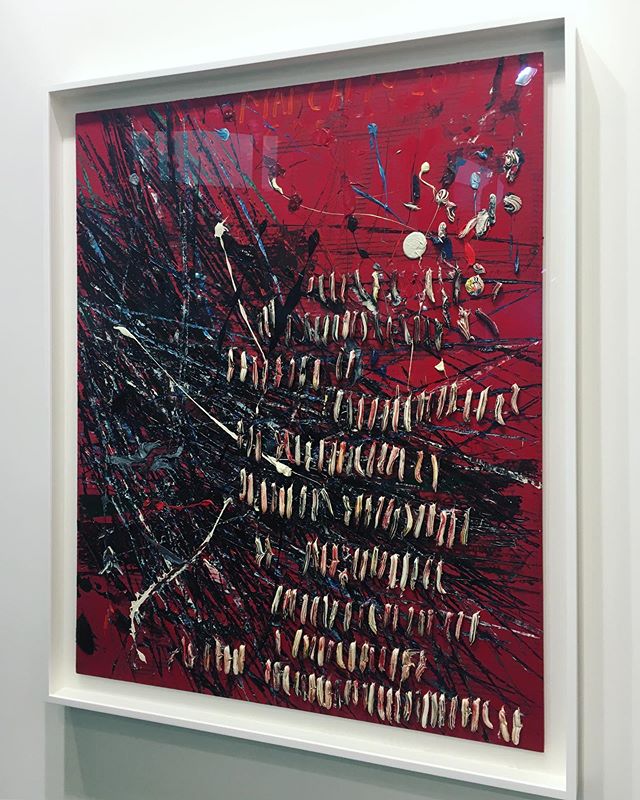

In the final space, in striking contrast, life-size works confront the viewer. In Polidoro da Caravaggio’s painting Incredulity of Saint Thomas (1531-35), the disciple demands tangible proof of Christ’s resurrection. Alongside, Siobhán Hapaska’s Saint Christopher (1995) is a disturbingly real and immediate physical presence. Elsewhere, Adam Chodzko’s Secretors (1993), blood-red droplets of ‘manifestation juice’, are a subliminal presence, a ‘seepage from other realities’, as the artist describes them.

This innovative exhibition offers the opportunity to experience rarely-seen and diverse works in unusual and provocative conversation.