Sotheby’s London

29 June 2011

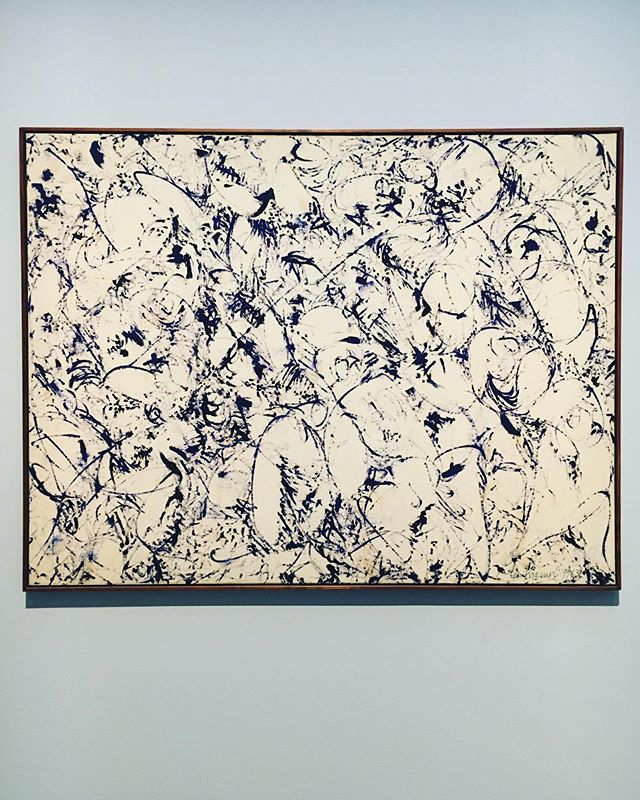

Deriving from the early period of his highly influential career, Mädchen im Liegestuhl (Girl in Deckchair) is a stunning photo-painting that exemplifies the quintessence of Gerhard Richter’s oeuvre. Exceptional on account of its very early date and its flawless execution, the work’s ethereal beauty also carries an underlying intellectual rigor that helped re-define contemporary painting, as well as conceptual genres.

Painted in a blurred, quasi-Impressionistic manner, Liegestuhl vacillates between figuration and abstraction, as it dismantles into a matrix of semi-abstract marks when viewed at close range. The geometric shape of the deckchair invites the viewer to take a step back; suddenly, the image seeps into our consciousness and grows in stature and complexity as we perceive it from afar. Richter’s strong pattern of lateral striations and sfumato blurring of contours give the work its delicate beauty. The brushwork is gracefully fluid: each individual stroke is lightly feathered into another, creating an alluring surface that undulates before the viewer. As if catching a glimpse of a passing moment in our transient world, the image is rendered a fragile illusion.

In the early 1960s, fast-paced mass-media photography replaced pictorial memory. This technological revolution had a direct impact on artistic production. The new form of visual art that appeared broke with tradition, as it incorporated the regular flow of press images. Following in the footsteps of American Pop artists, such as Rauchenberg, Warhol and Lichtenstein, Richter began using mass media images as a source for his work. This strategy of appropriation engaged with Duchampian debate, and to a certain extent with Walter Benjamin’s writings, as it subverted traditional artistic notions such as creativity, originality and high art in the age of reproducibility.

At a time when artists were putting down their brush in favor of less traditional approaches to artistic creation, Richter remained committed to the expressive power of easel painting, producing works as radical as the source photographs on which he based his oeuvre. Hence, the artist’s formal approach to image making was essentially removed from the mechanical processes of Warhol’s silkscreen and Lichtenstein’s pixilation. While Liegestuhl offers the image a photographic appearance, it bears witness to the painter’s actions; thus lending an aura to the photographic vision.

Shortly after its creation, Liegestuhl was shown in the milestone exhibition Neue Realistsen, Richter, Polke, Lueg, held in 1964, at Rudolf Jährling’s Galerie Parnass in Wuppertal. This exhibition was considered by many the pinnacle of the Kapitalistischer Realismus movement, within which Richter’s photo-paintings from this period are often classified. Occasionally satirical in their approach, the Capitalist Realists appropriated the pictorial shorthand of advertising. Depicting the mundane through ghostly blurred photographs, the movement sought to communicate a different intention to American Pop by representing a broader experience, a wider view of reality. This significant distinction is epitomized in Liegestuhl, as the source image finds its roots in the banal activities of everyday life.

The composition of Liegestuhl was sourced in a photographic image from a 1962 German newspaper, illustrated on page five of Richter’s monumental cataloguing project Atlas. In the foreground, the work depicts a carefree woman lying in a deckchair among nature’s elements: earth, sea and sky. At first glance, the photograph may seem innocuous and prosaic; however, upon closer inspection, one realizes that we are peering through the subjective lens of Richter’s social agenda. Hence, although the work emanates feelings of freedom and serenity, it is also a powerful commentary on German bourgeois life of the early 1960s.

The artist revisits this theme in 1965 with Liegestuhl II. While there are marked similarities between the composition and subject matter of the two paintings, notable differences emanate – namely, the anonymity of the figure depicted in Liegestuhl I. The viewer craves to see the woman’s face and to have a human connection with her. However, Richter chooses to deliberately blur and distort his subject, draining her individuality from the painting and merging her with the upcoming wave. The artist’s blurring technique significantly alters the language of the photograph, consequently subverting its meaning. ‘I blur so that nothing will have an overdone, artistic look, but instead will be technical, smooth, perfect. Maybe I also blur the superfluous, unimportant information’ (Richter, Textes, p.32). In Liegestuhl, only the message remains, the subject is nullified and thus no longer stands for herself but becomes the personification of middle-class capitalist life in Germany at the time. This poignant tour de force acts as both a painterly and cerebral response to the societal climate of Western Europe in the early 1960s, as it actively engages with both identity politics and aesthetic theory.

Simultaneously creating and obscuring a fleeting moment, Liegestuhl is an evocative image exemplifying Richter’s virtuosity with paint. Testifying to much more than a visually reported fact, the painting does not merely document mass-media data, it presents the viewer with a unique cultural commentary. Richter’s fastidious manipulation of this image constituted his own distinctive version of Pop, which challenged the cultural presumptions of the 1960s and still remains relevant today. Mesmerizing the viewer, Liegestuhl confirms Richter’s place as a highly pivotal figure in Contemporary art.